- Home

- Sharon Biggs Waller

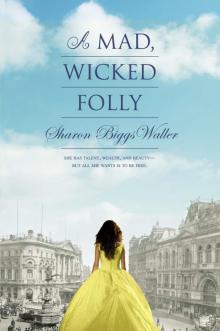

A Mad, Wicked Folly

A Mad, Wicked Folly Read online

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA • Canada • UK • Ireland • Australia

New Zealand • India • South Africa • China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published in the United States of America by Viking,

an imprint of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2014

Copyright © 2014 by Sharon Biggs Waller

Map courtesy of MAPCO: Map and Plan Collection Online—mapco.net

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting

writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Biggs, Sharon, date–

A mad, wicked folly / Sharon Biggs Waller.

pages cm

Summary: In 1909 London, as the world of debutante balls and high society obligations closes in around her, seventeen-year-old Victoria must figure out just how much

is she willing to sacrifice to pursue her dream of becoming an artist.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-101-61441-9

[1. Artists—Fiction. 2. Sex role—Fiction. 3. Love—Fiction. 4. London (England)—History—20th century—Fiction. 5. Great Britain—History—Edward VII, 1901–1910—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.B4837Mad 2014 [Fic]—dc23 2013029858

Version_1

For my aunt, Shirley Atchison Steinert. Thank you for believing in me and for being my very first editor, all those years ago.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Epigraph

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

Forty

Victoria’s Favorite Pikelets

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

I am most anxious to enlist everyone who can speak or write to join in checking this mad, wicked folly of “Women’s Rights” with all its attendant horrors, on which her poor feeble sex

is bent, forgetting every sense of womanly feelings and propriety.

—Queen Victoria, 1870

One

Trouville, France, Monsieur Marcel Tondreau’s atelier,

Monday, first of March, 1909

I NEVER SET OUT to pose nude. I didn’t, honestly. But when the opportunity arose, I took it. I sat with the other artists that morning in Monsieur Tondreau’s tiny atelier in the French village of Trouville waiting for Bernadette, our usual model, to arrive. Some tinkered with their charcoals and pencils; others adjusted their easels. A few of the artists stared at the stage as if the model would magically appear if they looked hard enough. Monsieur bustled around in his canvas smock, moving the model’s chair into the light, plumping the bolsters. The studio smelled of turpentine, linseed oil, and charcoal, and there was no sweeter perfume in the world to me than that.

Étienne, one of the other artists, yawned, leaned back in his chair, and closed his eyes.

“Hungover, old fellow?” his friend Bertram whispered. “Is fair Bernadette in the same state?”

Étienne grunted a warning but did not open his eyes.

“Poor Étienne,” I whispered. “He looks unwell, Bertram. Let him be.”

Bertram reached for his pencil, sharpened it with his knife, and began to sketch a cartoon of Étienne. “It’s hard to feel sorry for a chap who has inflicted illness upon himself and caused the malaise of our model, once again.” He added devil’s horns to the line drawing and then nudged Étienne’s boot with his own. Étienne cracked open one bloodshot eye and then closed it. “He lacks the artist’s discipline but possesses all of his foibles.”

“We all have our faults, Bertie.” I knew I shouldn’t side with Étienne; he was a rapscallion. But I also knew him to be a talented artist, and this, in my eyes, meant he’d earned the right to roguish behavior every now and then.

“If he had half your discipline, my dear Vicky, he would be lucky,” Bertram said.

I smiled and began my own sketch of Étienne, this one with angel’s wings. Bertram saw what I was doing, grinned, and shook his head.

I had made Bertram’s and Étienne’s acquaintance last autumn when I was drawing my dearest friend, Lily, in the village square. They plonked themselves down at our table as though we knew them and watched me as I worked. I was about to tell them to keep to themselves when Bertram blurted out, “You’re very good.” But then he spoilt it by adding, “For a girl.”

After I found out they were students of a local artist, Marcel Tondreau, and studied with him at his atelier, I wouldn’t let them leave until they told me about him. I was self-taught, apart from a few watercolor classes at finishing school, and I had always longed to attend an atelier like that, but my parents did not approve of such a thing. I begged Bertram and Étienne to introduce me to the artist. To my delight, I found that Monsieur was a rare person in the world of art. He didn’t care if the artist was male or female; he let the work speak.

All of the other artists at the atelier were male, and none of them gave me a thought apart from the occasional curious glance. I did not blame them. Most females drew things that did not matter.

But the other artists were wrong about me. I didn’t fill my head with airy nothings or paint watercolors of kittens and flowers meant only for decoration; I wanted so much more.

When I was ten years old, I laid eyes for the first time on a painting called A Mermaid, which hung in the Royal Academy in London. The mermaid’s eyes seemed to call to me, telling me that creating someone like her was within my grasp. And like her maker, J. W. Waterhouse, I wanted to be considered among the best artists in the world. I wanted critics to laud my work. But most of all, I wanted to express myself through my art as I fancied, and not be told what or whom I could draw or paint. For all of these dreams I needed knowledge and connections with other artists who could introduce me to the mysterious society that made up the art world.

No one at my boarding school, Madame Édith’s Finishing School for Girls, knew I attended the atelier—not the headmistress nor any of my fellow students, apart from Lily, who helped me sneak away. If they knew, it would be hell’s delight, because Monsieur Tondreau’s atelier was not the kind females should frequent. At

Monsieur Tondreau’s we drew from the undraped figure—the nude. No woman of good breeding would ever do such a thing, which was another reason why female artists were not taken seriously. Sometimes women could draw from nude statues without fear of scandal. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London held drawing classes for women, but the instructors covered the male statues’ bits with tin fig leaves. Apparently, gazing at a statue’s male anatomy was equivalent to staring into the sun.

Monsieur Tondreau glanced at his pocket watch and sighed. “Alors. I think that Mademoiselle Bernadette will not be with us today.” He leveled a look at Étienne, who was cradling his head in his hands. “So. We say good-bye for the day, or we have a student pose.” Monsieur’s gaze flitted over the artists briefly and then lit on Bertram.

“I’m not doing it again.” Bertram raised his voice over the artists’ calls of encouragement. “Once was enough.”

“Who wants to draw your scrawny carcass again anyway,” came a voice from the back of the room.

“I nominate Étienne,” Bertram went on. “He’s the cause of all this grief.” He stood up, grinning, and dragged Étienne to his feet by the shoulder of his jacket. Several students shouted out in agreement. Étienne took this all in humor for about ten seconds before slapping his hand over his mouth, turning a very sickly shade of yellow, and running for the back door that led to the outdoor privy. Sounds of retching echoed through the room.

“Can you not find a model who resists Étienne’s charms, Monsieur?” one of the artists asked. “This is the second time Bernadette has failed to show after a night out with him.”

“I’m sick to the back teeth of drawing the blokes,” Bertram added. “Hell’s bells, I can draw my own phallus at home. We need to draw women, Monsieur.”

“I will try, but it is difficult to find women who are willing. Or one whose father will let her.” He looked over the group again, but his eyes did not fall on me. “If no one will volunteer, then I shall bid you all farewell. À demain.”

“Why does she not pose?” demanded Pierre, a burly artist from Paris, who had pointedly ignored me from the day I walked into the studio. “Everyone here has had a turn. Why not her?”

I twisted in my seat and scowled at him. “My name is Vicky!”

Pierre shrugged. “I only learn names of people who matter, Vicky.”

“Don’t be an ass, Pierre,” Bertram said. “She’s just a girl.”

There it was again: I was just a girl.

“Pardonnez-moi!” Pierre replied. “I thought she was an artist. She pretends to be.”

I turned back in my seat and stared at my easel. I felt the gaze of several of the artists fall upon me. Everyone in the room had posed before. Everyone but me. And that awful voice inside me started up. That little voice that always carped at me when I didn’t feel confident about my work: No wonder none of the artists give you a thought. Why should they? You aren’t really one of them.

It was true, wasn’t it? I wasn’t willing to do what the other students did for art. Who was I to call myself an artist? If I didn’t take my turn, then I would always be just a girl. Certainly never an artist in the other students’ eyes. And then the words burbled out: “I’ll do it! I’ll pose.”

Monsieur Tondreau’s whiskered face registered surprise.

Pierre looked taken aback for a moment, but then I thought I saw a little flicker of respect in his eyes. “Well, then, mademoiselle. I was wrong. Maybe you aren’t pretending, after all.” He bowed slightly, sat back down in his chair, and began to set up his easel.

“I didn’t mean you, Vicky,” Bertram said.

I stood. “The other artists here have taken their turn. Pierre is quite right. I should do my bit.”

“A moment, gents.” Bertram took me by the elbow and led me off to the corner. He leaned in close. “Vicky, you know female models have more to lose than male ones. No one cares if a bloke gets his kit off.”

“If I’m going to be a student here, treated on equal terms, then I have to be willing to do everything that they do,” I said. “There can’t be two sets of expectations, one for them and one for me, the only girl in the class. How will I earn their esteem if I don’t pose?” I threw a glance over my shoulder at the students watching us. Pierre sat with his arms folded; the look of respect was now replaced with a sneer.

“Are you going to try to tell me that you care what Pierre thinks? That great buffoon? The only one you should care about is Monsieur Tondreau, and he thinks the sun shines out your arse. Take my advice: let your fabulous work speak for you, and forget about what everyone else says or thinks. Pose if you want to, by all means, but don’t do it because you feel you have to. A model should never be forced; you know that, Vicky.”

“I’m not forced.” I jerked my arm out of Bertram’s grasp and marched to the front of the room. I wouldn’t say that I wasn’t afraid, because I would be lying. My legs were trembling so much I was surprised my knees didn’t clack together.

Mercifully, Monsieur came forward and helped me up onto the dais. He threw open the creaky blue shutters to let in as much light as the gloomy day would allow.

I am going to do this. I am really going to do this! I turned my back and let my breath out. I had no idea how to begin. When Bertram disrobed to model, he made it funny, pretending to be a fan dancer at the Folies Bergère, taking each item of clothing off and throwing it to us, eyes rolling comically while we whooped and shouted.

I decided to do the opposite, to act as if disrobing in front of a group of men was no great thing. I started to undo my blouse, but my hands shook and my fingers slipped off the buttons. I squeezed my hands into fists and tried again.

No one spoke a word as I undressed, but I could hear the usual bustle of artists readying their easels and drawing boards—the rustling of paper and the scrape of pencils against knives. I slid my skirt and petticoats off, put them neatly to one side, turned around and sat down on the chair. I stared at my bare toes for the longest time, unable to find the nerve to look up. It was the first occasion in my life that male eyes had seen my unclothed body. I’d never cared what men thought of me before, but now, sitting in front of their steady gaze, I wondered how they regarded my breasts, my hips, my legs. I found I wanted them to see me as beautiful. In my own experience I’d looked at the men’s bodies in that way when they posed. I was human, after all, and the model wasn’t a thing, a bowl of apples to be drawn.

Finally, I forced myself to lift my head. And I saw ten pairs of eyes looking back at me. I had no idea what Monsieur’s students were thinking, because they were professional and had learned to focus their minds on their work. They knew if they gave in to any urges—leering or making bawdy comments—Monsieur would dismiss them and they’d never be allowed back.

And so the artists regarded me frankly and then bent to their work. Only one of the newer artists, a boy about my age, gaped, his eyes out on stalks, jaw dangling. I could see his throat tighten when he swallowed. I met his gaze and raised my eyebrows. Startled, he knocked over his easel, his pencils and papers scattering over the floor, earning disgusted looks from the more experienced artists. He fumbled to gather up his things, his ears red.

Bertram remained in the corner with his hands in his pockets. I tilted my head toward his easel. He hesitated for a moment, opened his mouth to say something. But then he shrugged, went back to his workplace, and began to draw.

I felt my shoulders relaxing, my nerves disappearing. I felt like Queen Boadicea taking on the Romans. I leaned forward, propped my chin in my hand, and stared out at the boys.

Now I’m one of you.

WHEN THE CLASS was over, the students—apart from Étienne, who reeled off for home—asked me to join them at a nearby café, a place they all went after class to argue about art. They had never invited me before. I had a little time to spare before I met Lily where she always waited with my schoo

l uniform, so I went along.

The only other woman at the café, apart from myself and the proprietor’s wife, sat at a little table, a glass of green liquid at her elbow, staring straight in front of her, a dazed look on her face. Her booted feet were turned out carelessly to the sides, her knees wide apart. I had never seen a woman sit like that in public in my life. The art students paid her no mind, apart from Pierre, who grunted a greeting in her direction.

The artists noisily pulled several tables and chairs into the middle of the room, creating a table that would accommodate all of us. No one glowered at them or told them to hush up or to put the tables back. Instead the proprietor came over and shook everyone’s hands, then surreptitiously slid a large basket of crusty bread onto the table, despite the disapproving glare of his wife. Several of the students fell on it, grabbing the bread with their bare hands. I knew it was probably the only meal they would have that day. Bertram had told me that many of them spent their extra money on paint—and wine—instead of food.

The proprietor returned with a carafe of red wine. I could not return to school with wine on my breath, so I asked for coffee.

Pierre poured a glass of wine and stood up, holding the glass in my direction. “À la vôtre! To Mademoiselle Vicky! For . . . how do you say in English . . . saving the day!”

The other artists held up their glasses; some banged the table; a few clapped.

I pretended it was nothing, but I knew I would hold their acceptance close forever, like a treat I could take out and savor anytime I wanted.

The conversation turned into an argument. This one was about whether painting subjects like a mother and child was maudlin pap. Bertram said it wasn’t; Pierre said it was.

“What do you say, Mademoiselle Vicky?” Pierre asked, squinting at me through a plume of cigarette smoke.

“Ça dépend,” I said, carefully, knowing that Pierre fully expected me to launch into a statement about how lovely a mother and child were to look upon. “It depends upon what you’re trying to say, what emotion you want to conjure within the viewer. If you render your point of view skillfully, even the simplest subject can have meaning and purpose.”

Girls on the Verge

Girls on the Verge The Forbidden Orchid

The Forbidden Orchid A Mad, Wicked Folly

A Mad, Wicked Folly